Understanding neurodiversity and cognition is an essential tool to deliver the best practice neuro-inclusion and support.

In this guide, we outline the background of Cognassist’s digital cognitive assessment in education and our basis of validity.

And explain how we ensure, with scientific accuracy, that no learner is left behind.

What’s included:

- The science behind our digital cognitive assessment.

- How support is delivered to learners who identify with a learning need.

- How we plan our personalised learner journeys.

- Our best evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of our personalised learning strategies.

A guide to the science and development behind Cognassist

Many educators will be familiar with Educational Psychologist reports, but perhaps less so with the process of psychometric testing itself.

Cognassist is an organisation committed to breaking down barriers, not just for learners who require support, but for organisations and individuals looking to become more effective and data-driven in their support provision.

This guide will outline the background of Cognassist’s digital cognitive assessment, as well as comparative paper-based assessments on which our assessment is based.

We will discuss the science and research around cognitive assessments and our basis of validity that gives us the means to ensure, with scientific accuracy, that no learner is left behind.

How did you develop the assessment?

The Cognassist digital cognitive assessment was developed from established tasks within the fields of neuropsychology and cognitive science designed to measure important thought processes.

While traditionally paper-based, digital administration of cognitive assessment provides multiple advantages:

- Consistent scoring and administration of tasks that can be prone to human error, removing calculation errors, clerical errors or unintended interpretation bias of paper-based assessments (Styck, K. M. & Walsh, S. M., 2016)

- Precise control of stimulus presentation

- Decreased administration cost and greater accessibility to assessment

- Ability to collect large data sets for accurate control of difficulty levels

- Ability to collect larger and more diverse samples for the creation of normative databases

The tasks included in the Cognassist assessment were chosen by Dr John Welch and Dr Clive Skilbeck, based on over 40 years of clinical and research experience. Tasks were chosen to represent a broad spectrum of cognition, including memory, verbal ability, visual processing and processing speed – all known to be important in the learning and assessment process.

After task selection, the battery was piloted iteratively to ensure a normal distribution of scores and to create normative datasets. User experience was also piloted to minimise unintended use.

Since release, over 140,000 learners within the UK have completed the Cognassist assessment, enabling the creation of widely representative normative datasets. Normative samples are updated regularly to minimise changes in population distributions, which can shift over time.

Distributional properties are also regularly monitored, such as skewness and Kurtosis, to minimise and prevent any floor or ceiling effects.

How do you know the assessment assesses what you want it to assess?

A leading model of human cognition is the Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of cognitive abilities. This model outlines an empirically driven theory of cognition, which was created using multiple meta-analyses of data from various sub-disciplines of psychology such as educational psychology, neuropsychology, cognitive science, neuroscience and clinical psychology.

The tasks included in the Cognassist battery have been mapped onto the CHC model to track the broad reach of the tasks selected and create an evidence-based assessment.

Inter-correlations between tasks are analysed using a standard statistical validation technique called factor analysis. Factor analysis helps to match batteries of cognitive tasks to scientific theory such as CHC. Cognassist tasks load onto expected factors including verbal, memory and visual factors. Correlational analysis, as well as factor analysis has shown that the Cognassist assessment measures cognitive abilities that are related but distinct, as expected from scientific theory.

These individual tasks are well-established within the wider world of psychology and have been used in various controlled settings for many years, developing a large body of evidence for what they measure. For example:

Child development studies – cognitive tasks are used to learn about how children’s minds and academic skills develop and change over time. They are also used to identify potential learning difficulties early on.

Longitudinal studies – seeing how people’s cognition changes over time by using the same tasks, as well as looking at how life events and lifestyles impact cognition over a lifetime.

Work with brain lesion patients – cognitive tasks are used to help diagnose brain injury, but brain injury patients also help us understand human cognition itself when we research which capacities are spared/affected when specific areas of the brain are injured.

Measuring brain activity – looking at brain activity helps researchers understand which cognitive capacities are related to each other and which aren’t, as well as helping us understand which processes are involved in a particular task. As a simple example, if we think a task relies heavily on visual processing, we should see the visual cortex light up in an fMRI machine when we measure the brain activity of somebody completing the task.

Brain pathology research (focusing on Dementia, Parkinson’s and strokes) – cognitive tasks are used to help diagnose pathology but also to understand it. By investigating which cognitive capacities are affected by a disease, we can understand which parts of the brain are being affected. We can also use them to track the progress of a disease.

This helps to give us a very rounded picture of what’s being measured and creates a strong basis of validity grounded in the practical application of research into brain function.

For many learners, understanding how their brain works can be a life-changing revelation that validates a lot of what they’ve experienced previously in education and helps them to learn in a way that works for them.

This requires accuracy and careful processing of data, which would not be possible without our science team and some fantastic consultants who are renown in the field of cognitive research.

27 workplace adjustments to support neurodiversity

Top tips to empower different thinkers in your organisation and break down barriers in the workplace.

Download nowHow does it compare to other assessments available?

Cognassist’s assessment is similar to many cognitive assessment solutions available in the western world, as the field of cognitive assessment is quite well understood. Cognassist only differs because we use a digital, computer-based assessment, instead of paper-based, but this in itself is not unique as a few digital cognitive assessments exist in America.

Some of the most well-known paper-based assessments are the various Wechsler scales; we measure many similar cognitive attributes to these scales, and in some cases use a digitally adapted version of the same tasks.

Our assessment covers a broader range of cognitive abilities than many well-known batteries; however, we do not provide the level of detail required for a diagnosis of learning difficulties like dyslexia, dyspraxia, ADHD and dyscalculia.

Slightly different assessments are used for measuring cognition in children and adults. The Cognassist assessment uses tasks suitable for adults aged 16 and above only.

Why do you use standard scoring (or normal distribution) to measure people’s abilities in each domain?

Standardised tests are used for multiple purposes in education, including when we measure cognitive abilities. We transform scores into what are called standard scores, which allows us to compare results between different tasks, between people and control for age.

As everyone takes the same assessment through Cognassist, we need to compare each person to others of their age, so we can measure relative performance effectively – it’s not scientifically relevant to compare cognitive scores between 16-year-olds and 64-year-olds.

Standard scoring is a recognised method that allows comparisons of results and is the primary mechanism proposed by both global canons of psychology; the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases version 11 (ICD-11) and the American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version 5 (DSM-5). No matter the task, standard scores have an average score (or mean) of 100, higher than 100 being above average and lower than 100 being below average.

Transforming scores to standard scores also results in a standard deviation of 15. This is where the threshold of 84 comes from.

A standard score of 84 is essential when identifying a need because this score is just beyond one standard deviation below the mean; a point which is recognised to be scientifically significant and below which an individual can be considered to be at a substantial cognitive disadvantage compared to their peers.

Standard scores conform to what is known as a normal distribution. In a normal distribution, 68% of the population will score somewhere between 85 and 115. About 16% of people will score below 85, and about 16% of people above 115.

Standard deviations are useful, because a score of one standard deviation or more below the mean (84 and below), suggests that that person’s score deviates from the population average more than a significant majority of people.

In a cognitive assessment, a low score will indicate a person having difficulties with this cognitive domain and it is likely they will require support for tasks involved in this area of cognition.

The Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) agrees with this scoring.

The Access Arrangements and Reasonable Adjustments regulations and learner support criteria state:

“So as not to give an unfair advantage, the assessor’s report (Part 2 of Form 8) must confirm that the candidate has: at least one below average standardised score of 84 or less which relates to an assessment of:

- speed of reading (see paragraph 7.5.10); or

- speed of writing (see paragraph 7.5.11); or

- cognitive processing measures which have a substantial and long term adverse effect on speed of working (see paragraph 7.5.12).”

To top it off, a learning need is also defined within the Education Act 1996 as:

“the person has a significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of persons of the same age[.]”

Another reason why we use the age-standardised score to maintain validity and meet established criteria.

Can a learner access support if they identify in only one domain?

The Cognassist neurodiversity assessment has been designed to measure a broad spectrum of cognitive abilities, rather than a single, combined measure. These nine domains can and should be measured separately. Therefore, support should be given if a learner identifies in any of the domains. We can break this down further.

Within the CHC model, it is acknowledged that many of the domains of cognition are related, and often work together as we perform tasks, but still represent different abilities, which should be measured separately if we are to build a more comprehensive understanding of a person’s brain:

“[D]ifferent [cognitive] abilities do not reflect completely independent (uncorrelated or orthogonal) traits. However, they can, as is evident from the vast body of literature that supports their existence, be reliably distinguished from one another and therefore represent unique, albeit related, abilities (see Keith & Reynolds, 2012).” (Flanagan, D. P. & Dixon, S. G., 2014)

From statistical analysis of our own dataset, we calculated that the intercorrelations between each task are low to moderate (0.1-0.4). Some correlation is a good thing because it reflects our knowledge of how the brain works, and its inherently connected nature; however, lower correlations also show that each task is measuring a unique aspect of cognition.

What this is all building to say is that, if we know we can measure each domain separately and that they are indeed measuring different abilities, then we cannot withhold vital support when someone identifies with a need in one of these areas.

A lower score in a domain can represent significant challenges that often affects people’s performance in a specific range of tasks. Ignoring a low score in one domain means this learner will continue to struggle with this aspect of learning and thinking because they are not as effective in this type of information processing. They will also not benefit from strategies that could help them to rely on their strengths and mitigate the negative effects of areas where they struggle.

How to support neuro-different employees

A guide to cognitive differences and understanding neurodiversity in the workplace.

Download nowHow is support delivered to identified learners?

If a learner identifies in one or more domains, we provide them with a personalised learning support plan, based on their unique cognition and level of study. Once the tutor and the learner have agreed to this plan and had the initial conversations around their Neurodiversity Report, the learner will then start to receive four strategy modules each month for the duration of their programme to provide continual support.

This learning plan, which can contain over 100 tailored modules depending on the learner’s course length, will focus on different coping strategies that the learner can try out and embed into their work and study routines. These strategies target specific tasks, ideas or scenarios that people may find difficult and could potentially create barriers to success in their job role, personal life or study.

Each strategy looks at various approaches the learner can take to help them make better decisions and each is followed by an instruction to take action and implement some of these strategies in the workplace or study, usually over the course of a week. The learner reflects on this experience and the strategy and reviews it with their tutor during their next one to one session.

We always tell learners to be prepared to share their notes or thoughts with their tutor, which helps to create a more open relationship with their tutor, where they feel comfortable to talk about what’s working and what isn’t. This constructive discussion gets the learner involved in decision making around their learning experience and drives engagement. Plus, the tutor gets to see how the learner progresses and overcomes barriers to grow in confidence and skill – what tutor doesn’t want this for their learners?

The tutor’s role in this process is, of course, vital. In order to deliver the most impact from this support, we give tutors a simple but effective structure for one to ones with learners:

For example, if a learner created a mind map for one of the strategies and enjoyed doing it, the next steps here might be for the tutor to gently encourage that learner to use mind maps more widely and ask if they are still using them some weeks later. In this way, the tutor plays a role in the embedding process, reminding learners to keep at it until mind maps become a natural part of that learner’s routine.

Our framework of support starts out with more foundational skills and behaviours expected of learners and builds in complexity as the learner progresses through their course.

Our modules are designed to cater for both long courses, like apprenticeships, and short courses, such as adult learning courses. We design our support to have the maximum impact in the shortest possible time, by including soft skills as well as work/study skills as we feel these are equally important to learner success.

It’s all a process when it comes to learning and the more support a learner receives, the greater their chance of success.

How are strategies planned?

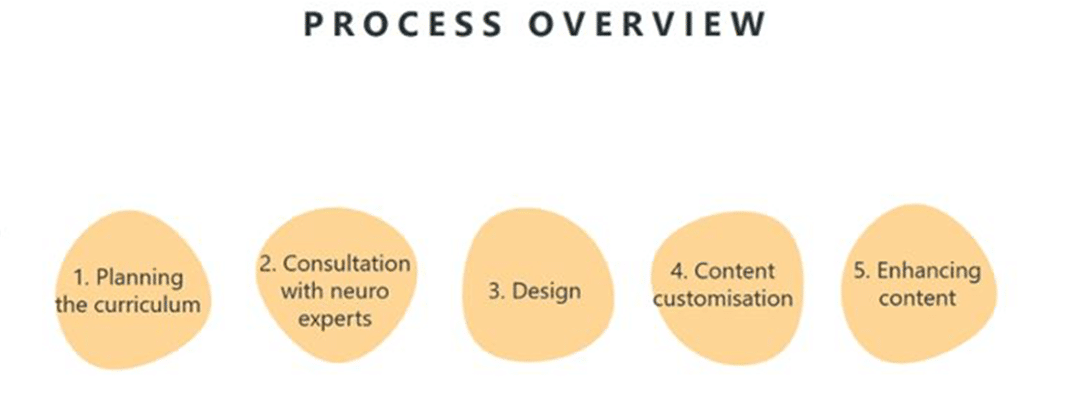

- Planning the curriculum

Within the standards framework, we identify common cross-disciplinary skills and behaviours at each level of study within further and higher education. For example, if a learner is studying at level 4 or above, we might focus on strategies that reflect certain managerial skills and admin tasks. We also focus on soft skills and effective study strategies to help learners better understand and implement skills that would be expected at their level of study but not necessarily taught directly as part of the core curriculum. For example, effective leadership and delegation skills.

For learners who match on our assessment, these soft skills and tasks may not be as intuitive as they are for others; providing them with step by step strategies helps to crystalise this information and build their confidence, which can have a direct impact on their likelihood of completion. - Consultation with experts

Our consulting neuropsychologists look at each strategy to define a level of difficulty, based on the different cognitive domains. They also identify which strategies will be the most beneficial for each learner, addressing the areas of learning they find most difficult to provide targeted interventions that give learners the best possible chance of success.

For example, a strategy on planning and organising work effectively is likely to be more relevant for learners who require support with executive function; however, it may also be relevant for learners who struggle with numeracy, which may be less obvious but no less adverse if not addressed. The relevance and difficulty of tasks is not always obvious, which is why we rely on scientists who have spent years studying the brain and how we think and learn. This step also informs how we design and write each strategy to better suit each learner. - Design

Our learning design team take over from here. They build each strategy into the platform using state of the art authoring tools with world-class credentials, which allows us to integrate multimedia options to support learning and present information in different ways to increase accessibility. - Content customisation

We use focus groups at each level of study to ensure our content is useful to learners and presented in an easy-to-understand way, tailored to each of the domains so learners are getting the most out of the content available. - Enhancing content

We regularly audit our learning strategy content to ensure it is still fit for purpose and reflects the demands of a learner’s chosen level of study. We also rely on learner feedback, built into each strategy module, to assess the quality and effectiveness of our content for those it is there to support.

Accessibility

Our mission is to make learning more accessible and improve the lives of learners who might otherwise struggle in education. We are constantly evaluating and refining our platform to drive this accessibility. We pride ourselves on keeping to high standards of both science and design to build a platform that’s intuitive and invaluable to learners and staff.

Our platform is measured against the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1), an international metric for web inclusivity, and our internal content and design guidelines have been structured around these best practice recommendations. As these recommendations are updated, we continue to iterate our platform to meet the principles of accessibility, usability and inclusion for all, using the best available knowledge.

It is the same for the science that fuels our assessment.

Modern cognitive science has only been around for about 140 years. As technology rapidly improves, our ability to measure and understand the brain increases. The human mind is still relatively unknown, we have no idea where consciousness itself comes from or how we develop our sense of self throughout our lives.

However, you can still provide valuable support to learners without solving the hard problem of consciousness.

What is clear to the scientific community and many educators who’ve used Cognassist, is that cognition plays a vital role in learning. It is the reason we are able to learn anything at all. Surely that’s worth knowing more about? To make learning more flexible and help tutors effectively identify learners who require more support early on in their learning journey.

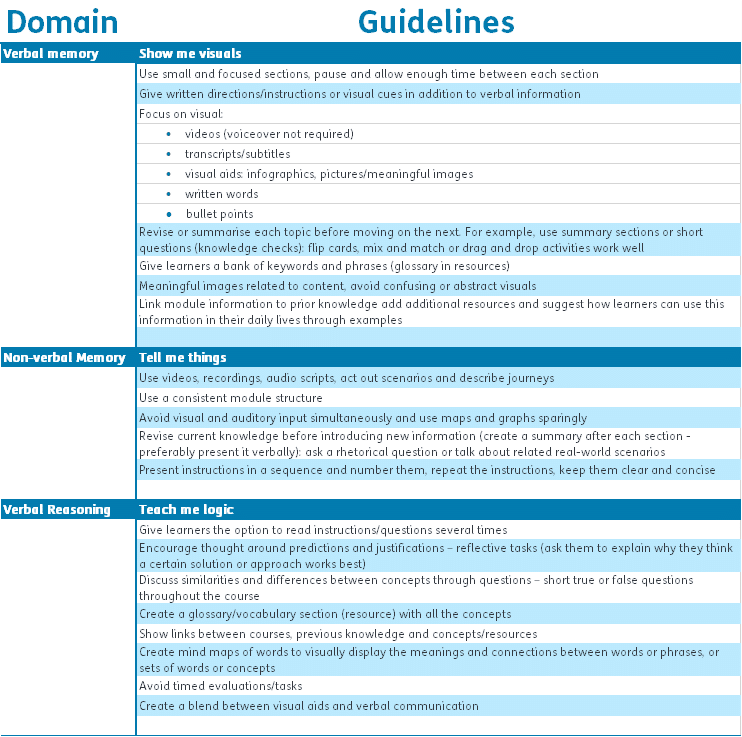

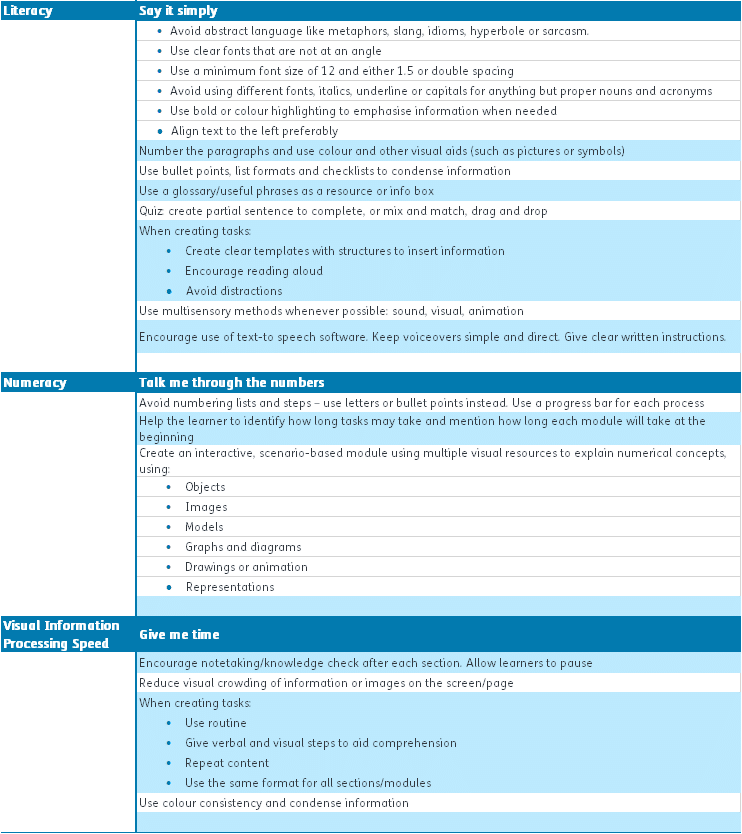

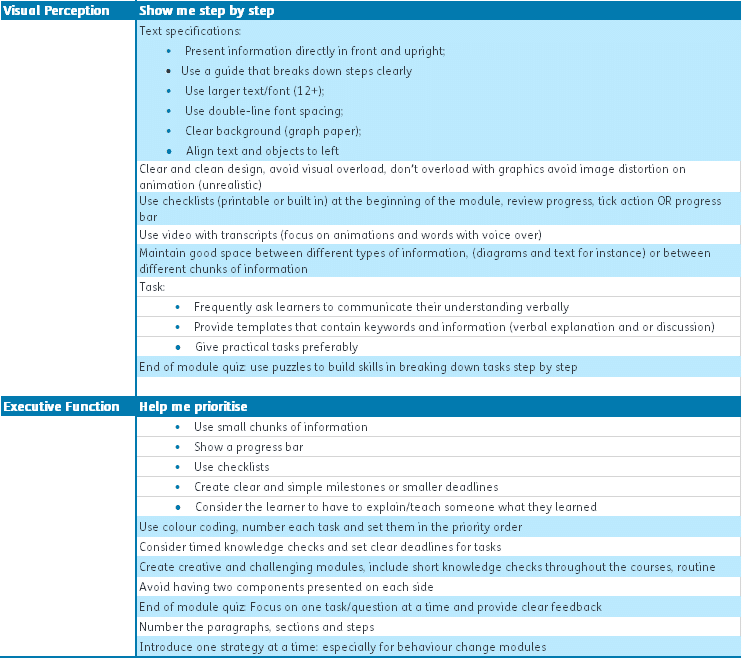

If you’re still looking for more, please take a look at our reference table below for an overview of specific rules we use to write, build and design each strategy based on these eight domains.

How do you know these strategies are effective?

As we mentioned, we are constantly gathering feedback from learners using Cognassist.

Each strategy has a feedback survey afterwards, and from 173,882 learner responses, we have found that 89% would apply the skill they learned to their work and study and 98% of the same number found their strategy useful.

The National Achievement Rate Tables (NARTs) shows the achievement rates of disabled learners or learners who experience learning difficulties (LDD).

Data from these tables shows that organisations that have used Cognassist for over two years have significantly higher than average achievement rate for their LDD learners – this is while having a larger than average cohort of LDD learners.

Even though they have more LDD learners, they still achieve higher than the national average, which goes to show that with the right support, more people are capable of achieving their educational goals.

And here are the numbers:

Data shows that LDD learners of Cognassist clients who have embedded the Cognassist assessment and support strategy tool into their processes had an average achievement rate of 70%, compared to the national average of 64.6% (an 8.36 percentage difference).

We’ve helped many clients increase learner attainment, like Bradford College, who increased LDD learner attainment by 10% in the NARTs in one year.

Some of our clients have achieved 100% achievement, so there is huge possibility for your learners to succeed and unlock their learning potential.

Hopefully, this gives you further insight into our platform, the assessment and learning support modules that have all been carefully designed to bring out the best learning experience and improve the lives of learners one step at a time.

How we can help

Cognassist helps businesses create inclusive workplaces by supporting cognitive diversity. Our platform identifies thinking styles and provides tailored strategies to boost productivity, engagement, and compliance. Partner with us to drive performance, foster inclusion, and meet regulatory requirements. Start building a more supportive and successful workplace.

Get in touch

Contact us today to discover how Cognassist can help your business support cognitive diversity, improve compliance, and drive performance.

Get in touch